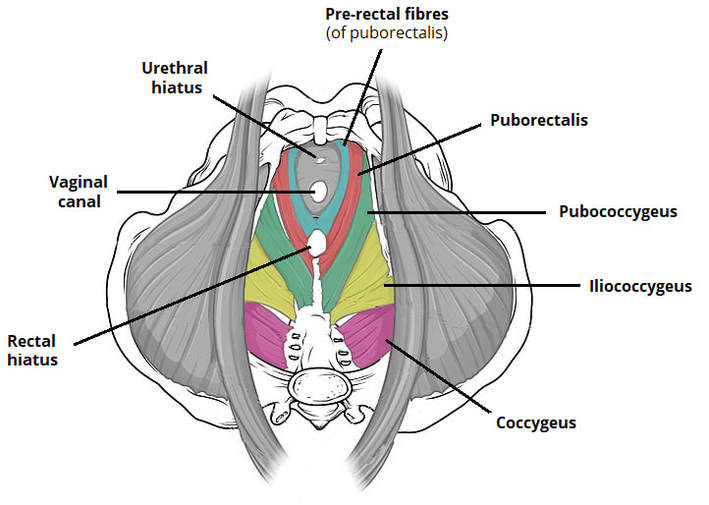

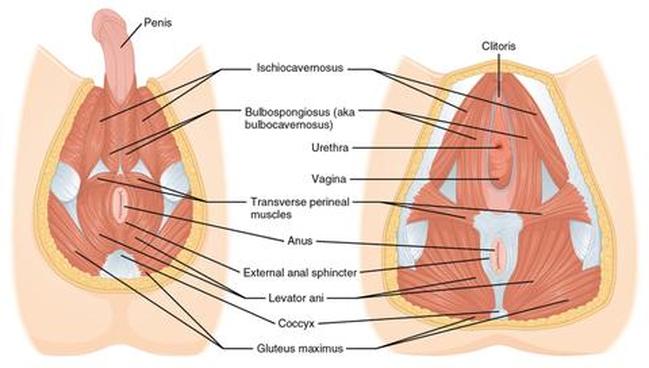

We ride through the physical world in meat suits composed primarily of water, with only a sparse set of more rigid support structures to frame out the vehicle. The bony basin in which the soup of our visceral contents sits is the pelvis, and at the base of the pelvis, supporting these contents and helping to regulate their excretion, lies what is commonly known as the “pelvic floor.” In reality, the pelvic floor consists of the perineal membrane and fascia, and a majestic muscle group known as Levator Ani. The Levator Ani can be further broken out into three distinct muscles: the puborectalis, pubococcygeus (which forms the pubovaginalis in women and the puboprostaticus in men), and iliococcygeus; however, these muscles function together to form a diaphragm-like sling that spans across the interior surfaces of the pelvic bones, wraps around the urethras of men and women alike, and whose fibers eventually become continuous with those of the anal sphincter. Together, they fulfill a role so vastly fundamental to the baseline functionality of our bodies that to address them separately in terms of location and biomechanical action alone would be to diminish their contribution to the human experience. In this paper I intend to explore these most crucial muscles as a group -- in function and in dysfunction, and in structural, psychological and energetic terms.

Structurally speaking, the Levator Ani performs a formidable task in supporting our entire pelvic contents and maintaining both urinary and anal sphincter continence. This means it is also responsible for maintaining optimal pressure within the abdominal cavity, which of course affects the function of the various organs it contains. In addition, Levator Ani makes an important cameo during childbirth, when its resistance is needed to control the descent of the presenting part of the fetus and rotate it to fit through the pelvic girdle. Weakness or injury to the Levator Ani can leave the unhappy subject incontinent, or even cause pelvic organ prolapse, when the bladder, urethra, small intestine, rectum or uterus protrude into the vagina.

It is not surprising, then, that many expectant mothers and other individuals who prefer to keep their organs unmerged practice Kegel exercises to tone and strengthen the pelvic floor. Invented first, surely, by early hominids -- and, successively and independently, by every being who ever possessed a fanny to play with -- but clinically debuted by Dr. Arnold Kegel in the mid twentieth century, Kegel exercises are simply voluntary contractions of the Levator Ani muscles.

As it turns out, however, Dr. Kegel was a bit of a gynecological Christopher Columbus in believing he was the first to distribute this wisdom and blazon it with his name. Jade stones or “Yoni Eggs” had been used to strengthen the pelvic floor and vaginal muscles for thousands of years before Kegel’s head ever rotated against his mother’s Levator Ani. Ancient Chinese royalty would exercise the pelvic floor by lifting jade eggs internally, seeking to harness the full potential of their sexual power. Awareness of the pelvic floor also appears in the ancient practices of Yoga and Pranayama. Mula Bandha, an energetic “lock” created by contraction of the Levator Ani, is a central practice in much of traditional Yoga. Nowadays, some Ashtanga Yoga teachers encourage constant maintenance of Mula Bandha, and some particularly avid students of modern Yoga have crossed the Jade Egg with bodybuilding and begun lifting heavy objects with these muscles, much to the benefit of their instagram ratings and, ostensibly, their sex lives.

It is not surprising, then, that many expectant mothers and other individuals who prefer to keep their organs unmerged practice Kegel exercises to tone and strengthen the pelvic floor. Invented first, surely, by early hominids -- and, successively and independently, by every being who ever possessed a fanny to play with -- but clinically debuted by Dr. Arnold Kegel in the mid twentieth century, Kegel exercises are simply voluntary contractions of the Levator Ani muscles.

As it turns out, however, Dr. Kegel was a bit of a gynecological Christopher Columbus in believing he was the first to distribute this wisdom and blazon it with his name. Jade stones or “Yoni Eggs” had been used to strengthen the pelvic floor and vaginal muscles for thousands of years before Kegel’s head ever rotated against his mother’s Levator Ani. Ancient Chinese royalty would exercise the pelvic floor by lifting jade eggs internally, seeking to harness the full potential of their sexual power. Awareness of the pelvic floor also appears in the ancient practices of Yoga and Pranayama. Mula Bandha, an energetic “lock” created by contraction of the Levator Ani, is a central practice in much of traditional Yoga. Nowadays, some Ashtanga Yoga teachers encourage constant maintenance of Mula Bandha, and some particularly avid students of modern Yoga have crossed the Jade Egg with bodybuilding and begun lifting heavy objects with these muscles, much to the benefit of their instagram ratings and, ostensibly, their sex lives.

Unfortunately, contrary to the Western mantra “More Is Better,” too much tone in the Levator Ani can also be problematic. Levator Ani Syndrome is another unfortunate dysfunction of the pelvic floor, whereby excessive tone can cause painful spasms in the Levator Ani muscles. So it is a balancing act we play in this foundational muscle group, seeking only the right amount of holding at all times.

Although it would be logical to assume that the Levator Ani is of most importance to bipeds, since gravity brings our viscera to sit in the pelvis rather than be supported by the bony thorax and the abdominal wall, the Levator Ani muscles are actually much stronger in quadrupeds, as they are primarily responsible for the action of tail-wagging. This evolutionary parallel gives an emphatic hint that this muscle group is not only mechanically important but also a strongly expressive body part in terms of emotion. As human tails have been reduced over millenia to a measly, un-waggable stump known as the coccyx, the emotional expression created by tone patterns in this muscle has become a much more internal one, though no less poignant. The rhythmic contractions of the Levator Ani are unmistakably present for humans of all sexes during orgasm. In my view, the ecstatic pumping release of sexual climax represents a perfect antithesis to the too-much and not-enough tonal issues we examined above. And indeed, a psychosomatic examination reveals that the ability to attain sexual satisfaction is very much linked to maintenance of appropriate tone in the pelvic floor, which in turn is deeply connected to psychological and personal history, attitude, and disposition.

In Bodymind, Ken Dychtwald superimposes psychological and kinesiological disciplines with Tantric energetic anatomy to posit that the pelvic floor, or the anal region of the pelvis (as opposed to the genital) corresponds to the muladhara chakra, which concerns itself with basic survival needs, primitive energy and human potential. He writes:

[Muladhara Chakra] is responsible for basic survival needs and actions, and, with the corresponding anal region, is said to be the vortex around which the energies and attitudes of primitive, material concerns revolve.

When a person is tense and tight in this bodymind region, it indicates that he is overconcerned with material and survival needs. As a result, he will have difficulty giving and taking in an unrestrained fashion and may try to hoard and possess everything with which he comes in contact. Conversely, when there is vitality and flexibility in this region, it reflects an open, giving, free-flowing way of being in the world. (p. 91)

Dychtwald further suggests that inefficient use of the muscles of the anal region during defecation is connected to emotional disturbance caused by imposing early toilet training on toddlers who have not yet developed adequate sphincter control. When children are forced to toilet train prematurely, they needlessly recruit many other unrelated muscle groups, including the pelvic floor. The result is that elimination becomes “a difficult and uncomfortable process that is unconsciously associated with bodymind tension and holding on and with an overriding inability to let go comfortably without activating an unnecessarily wide range of muscles and feelings” (p. 94). Thus the typical ‘anal retentive’ personality is linked to the bodymind significance of the Levator Ani as a muscle whose tone indicates the ability, or lack thereof, to allow experiences and emotions to flow through the body naturally.

This aligns well with the concept of sexual gratification as dependent upon the levels of both emotional and physiological tension in this region. In light of this, isn’t it logical that a person would have difficulty reaching an orgasm, or feeling sexually motivated at all for that matter, if he or she is holding in the first chakra, concerned with paying rent, buying food, or keeping a job? How can a person who is stuck in “hoarding” behavior engage fully in the give-and-take of lovemaking? And on a physical level, how is a muscle that is in a state of constant hypertonicity supposed to create joyful, strong, rhythmic pumping contractions to send blood, fluids and spirit into cosmic circulation? When we think of the human body not just in terms of the meat suit but all the Someone and the experience that it houses, muscles like the Levator Ani take on a hugely complex significance--both as products and creators of the human story.

In my own story, the Levator Ani has served as a teacher, a friend, and at times, played the proverbial Canary in the Coal Mine. Through the practice of Yoga and Pranayama, I have developed an awareness of this region that is more advanced than the majority of modern society, though I certainly have never lifted a surfboard with my vagina (c.f. Youtube). This journey of self-exploration through the pelvic floor not only gave me access to an immensity of untapped energy that lives within my system, but also brought me directly to the doorstep of many deep-seated fears and holding patterns that riddle my body and personality. The Levator Ani, and the practice of pranayama, continues to be a key part of my daily healing and self-reclamation practices. Though I would be a disappointing student of certain extra-emphatic Ashtanga teachers, the ability to recognize tension in this area of my body allows me to realize when I am contracting around the experience of the present moment. It is my sense that tightening the pelvic floor increases my internal pressure to match a real or perceived pressure from the external world, allowing me to feel myself more strongly and creating the illusion of enhanced self-support and bolstering. In a sense, when I contract my pelvic floor, I feel I am braced and ready --”armored,” as many would call it -- to face an anticipated difficult or jarring experience. Sometimes this is certainly a good plan. But more often than not, this response is a mechanism for shutting off sensation and possibility in the face of a danger that is more imagined than real.

When we consider all of this, The Levator Ani is clearly far more than a structural support or a mechanical sling; it represents fears and wounding, power and control, as well as openness and ecstatic surrender -- but only as long as we are able to consciously engage with it to eliminate skillfully on material, emotional and spiritual levels. It then becomes a most central and fundamental daily practice to cultivate a relaxed and toned, healthy pelvic floor, along with all its accompanying attitudes and dispositions.

Maya Cookson

IPSB ADM

RSS Feed

RSS Feed